Exploring Artists' Homes

Some artists use their home as inspiration, some decorate their homes with their art, and for others, their homes become their art. In Eppie's family, there's definitely a pattern of expressing creativity through their home interiors. Eppie grew up surrounded by colour and pattern in her parents' house. Now, in her own home, she has carried that on. It’s a patchwork of collected art, her own embroidery and needlepoint, and an ever-growing collection of beautiful things that spark joy.

It's always interesting seeing inside someone’s home, but seeing an artist’s home is something even more - it can offer a fascinating insight into their creative mind. We got to thinking about all the other artists whose homes can be regarded as works of art in their own right, and decided to put together a collection of wonderful examples - some of which you might not have come across before.

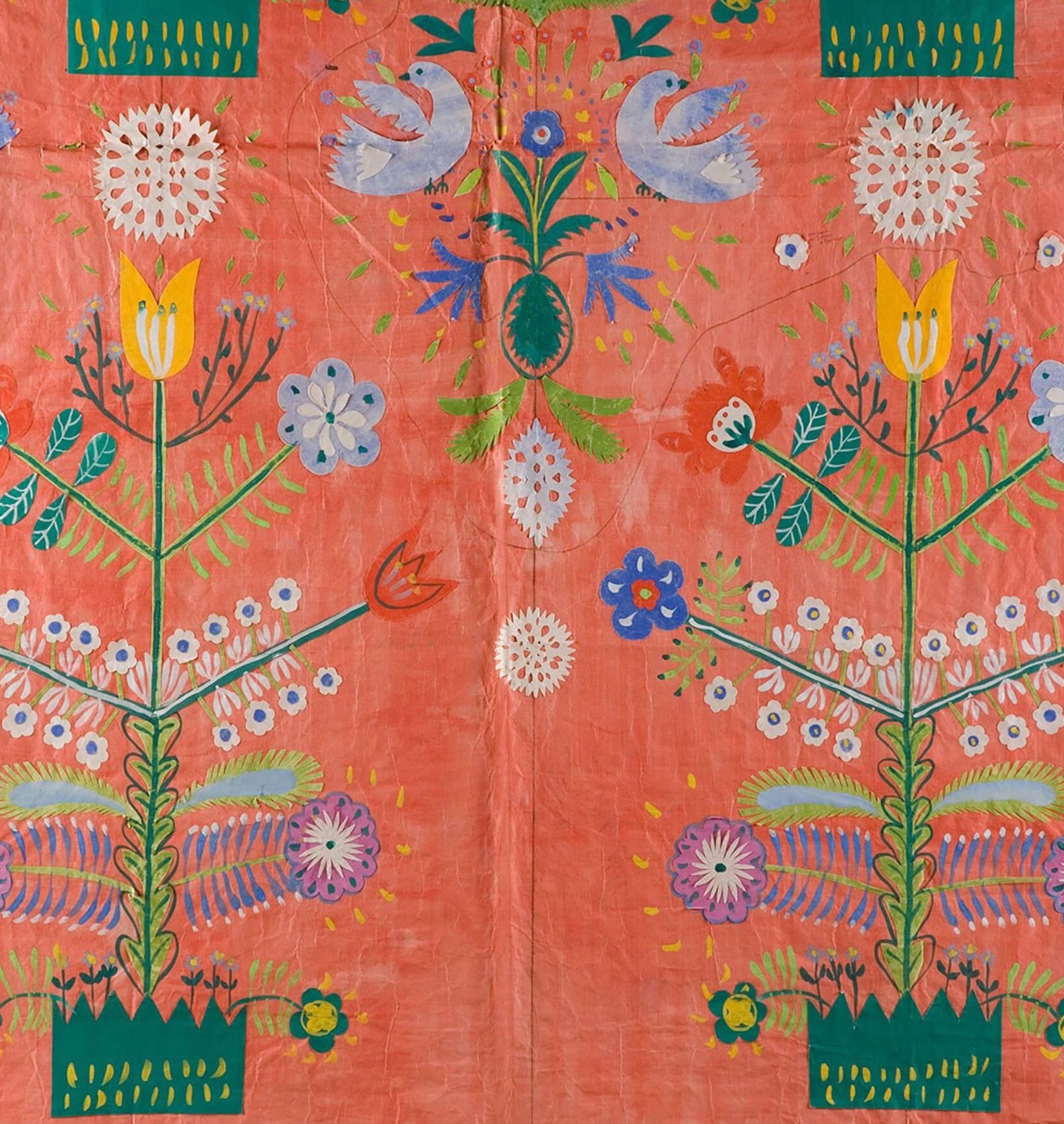

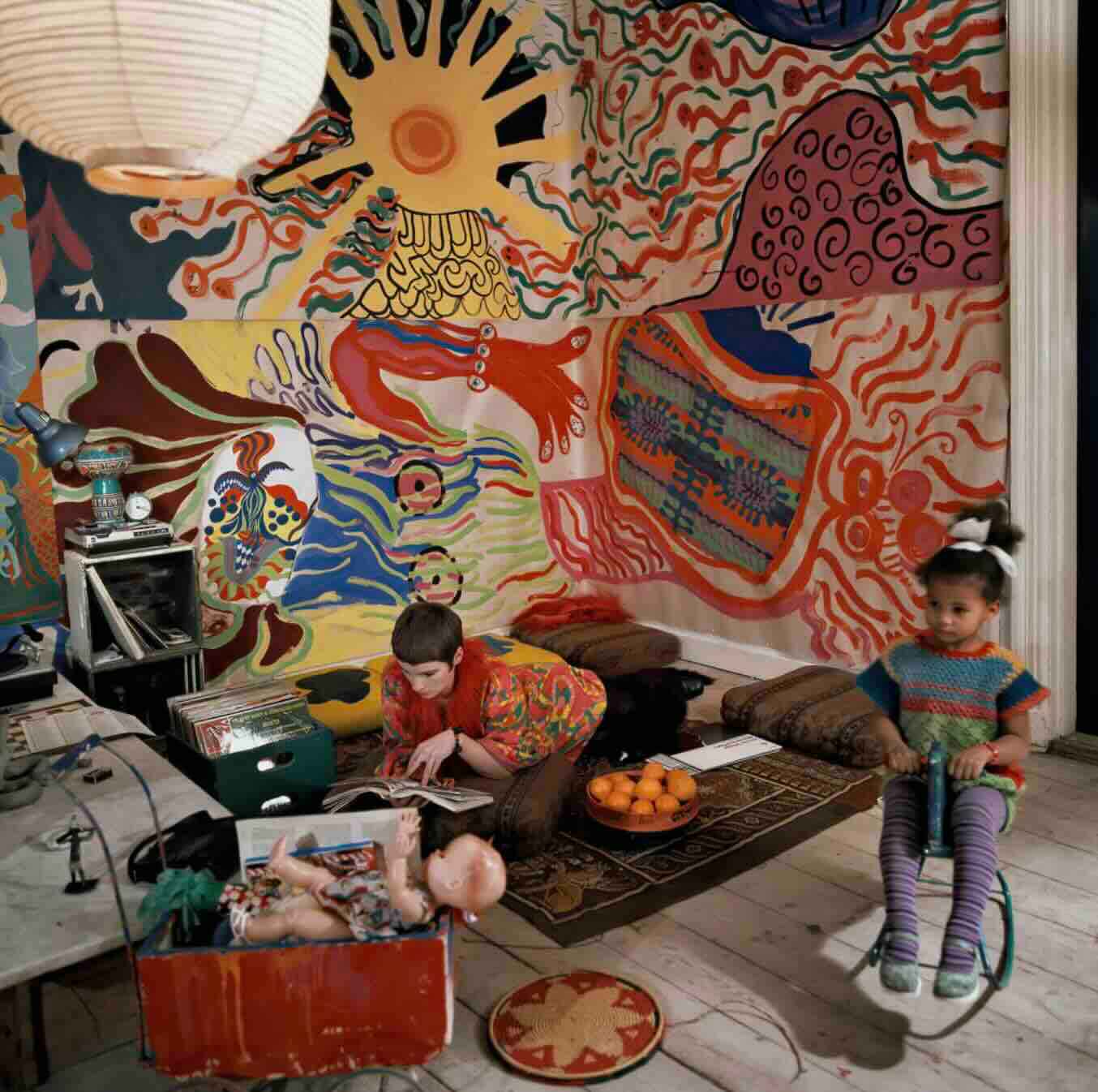

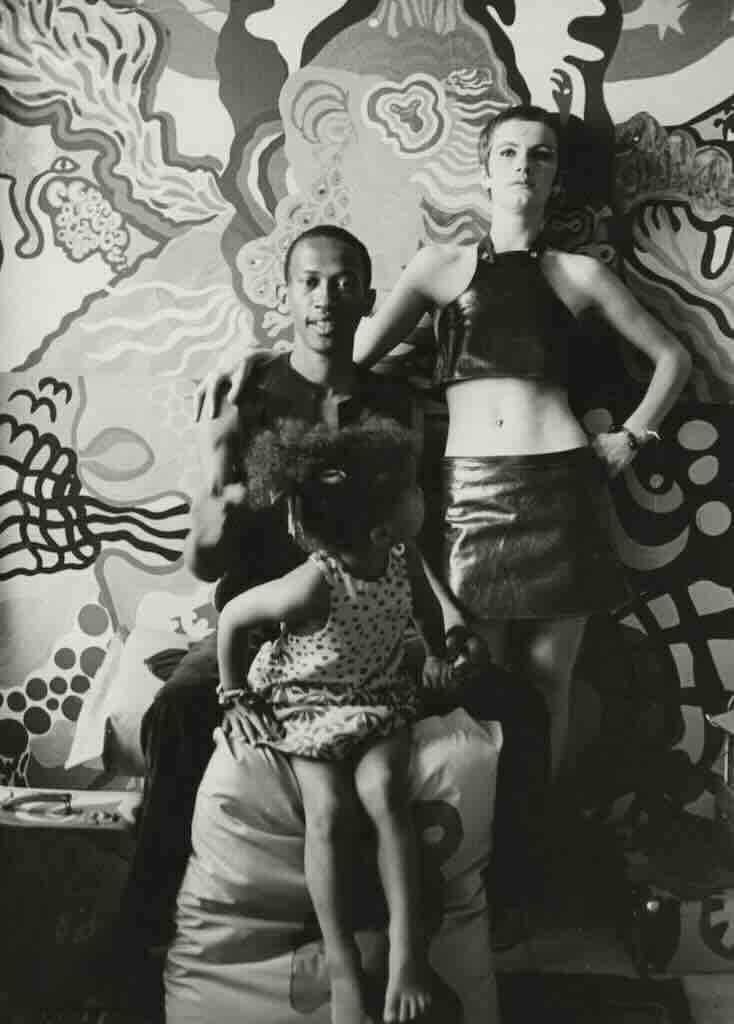

To begin, we'd like to share the story of the decorated homes of multimedia artist Moki Cherry, whose vibrant tapestries inspired Eppie's mum to start creating her own banners.

In 1968, pregnant with her son, Moki decided to paint the interior walls of her Stockholm apartment. She used swirling strokes of bright colour to transform her home into a new world in preparation for the birth of her son.

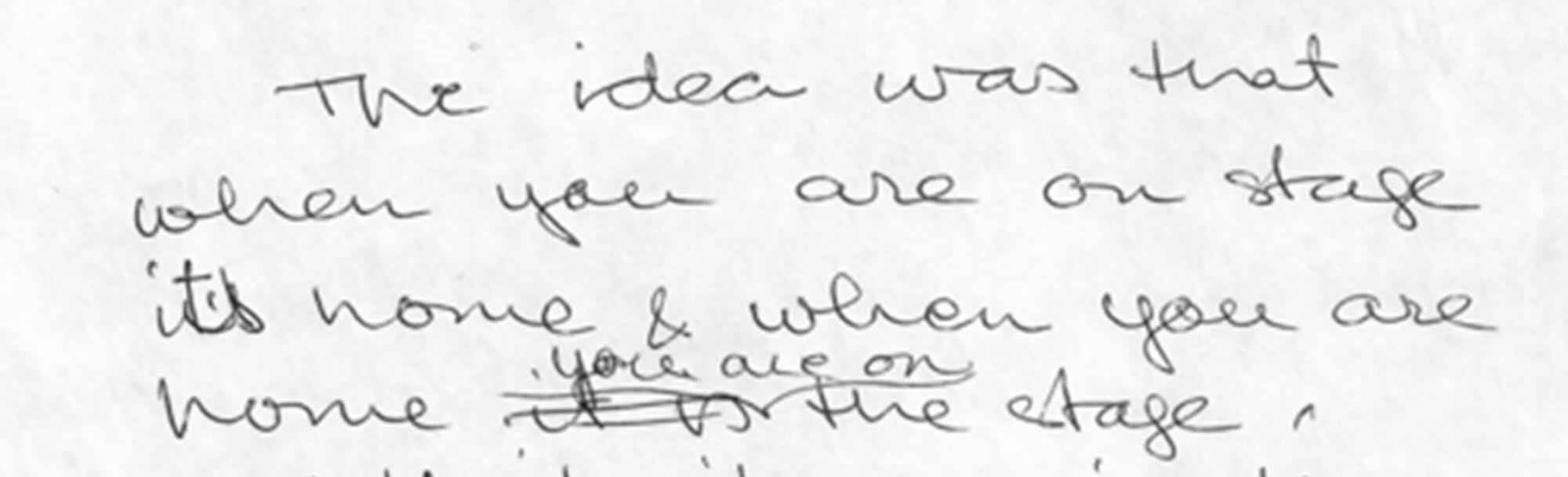

Moki viewed her home as a continuation of her art, and when she and her husband, the musician Don Cherry, moved into an old schoolhouse in 1970, this furthered the blending of the public and domestic spheres. The old schoolhouse became a public space for her husband to perform, with the couple hosting performances, workshops and exhibitions in their home. The blending of domestic and public life was a radical feminist stance even during a time when it had become more common for mothers to work. Moki’s philosophy was that the stage should be the home and the home should be the stage.

This philosophy seems to have had a significant impact on Moki’s family - growing up surrounded by music and art, Moki and Don’s children and grandchildren have gone on to become musicians themselves.

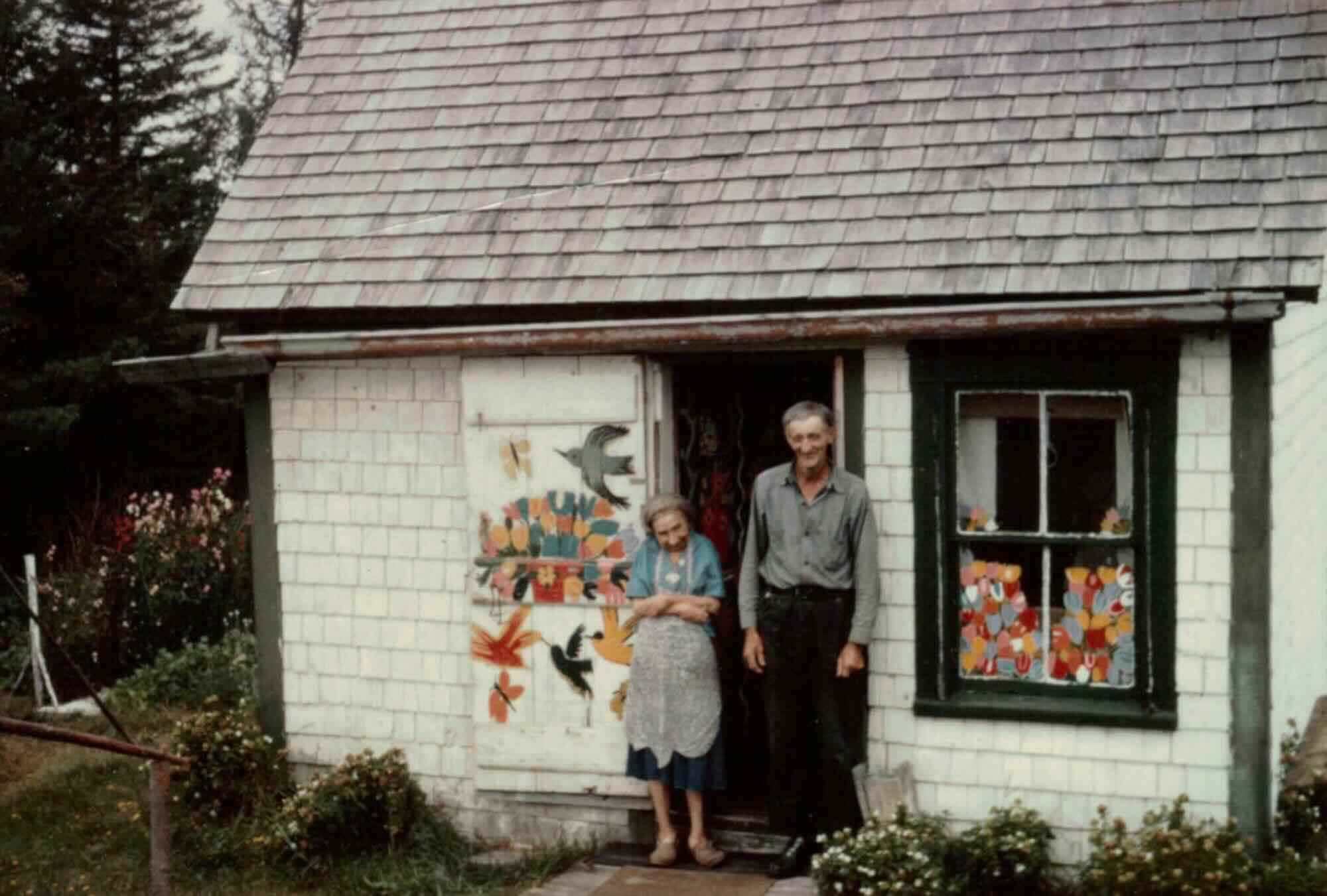

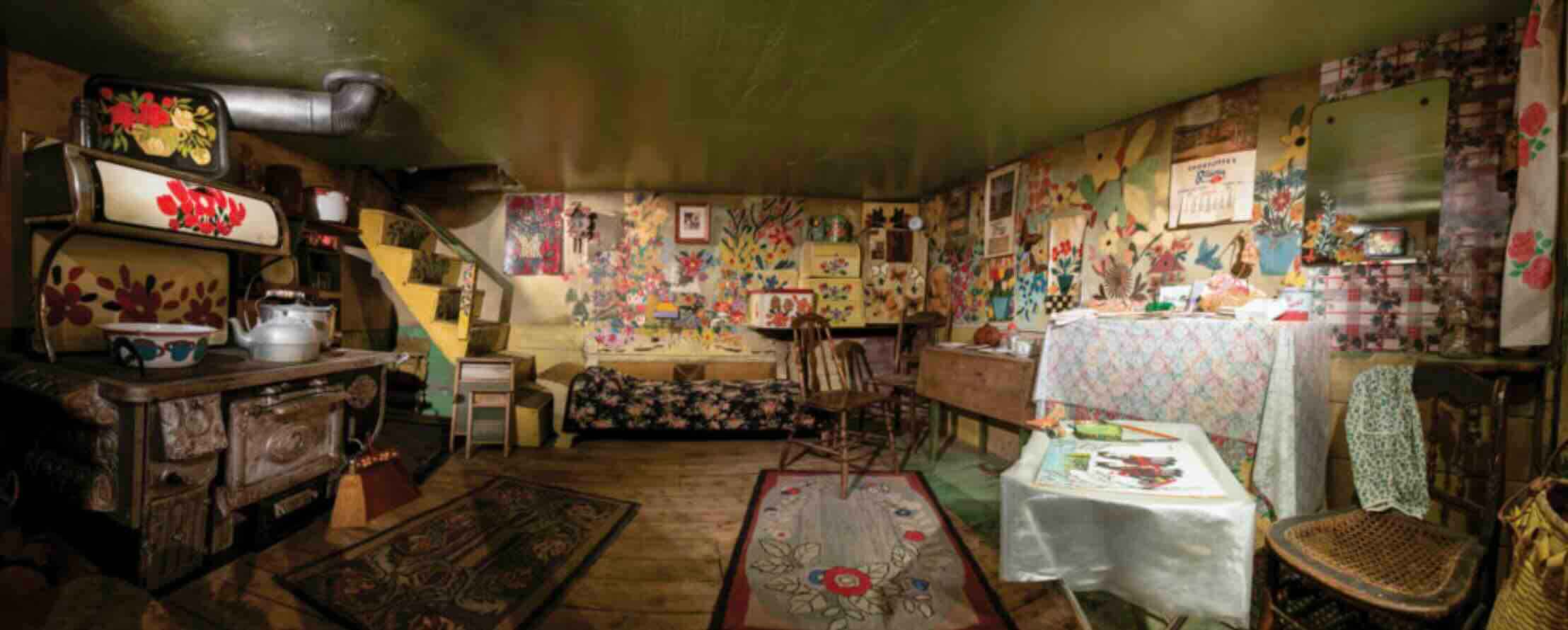

Canadian painter Maude Lewis’s home is perhaps her most famous work of art. Maude lived in a tiny house with her husband Everett, from 1938 until Maude’s death in 1970. She suffered from rheumatoid arthritis from an early age, and had taken up painting as a child. She was self-taught and sold paintings to earn money.

Though her paintings were often similar - she reused designs that sold well - her home shows us something more personal, things that she painted just for herself. Maude painted tulips on the windows, adorned the door with birds, flowers and butterflies, and painted murals of bright flowers. She even painted the stairs and the stove.

After Maude’s death, although Everett left the interior walls and furniture just as Maude had decorated them, he let the house fall into disrepair. When Everett died in 1979, a group of locals formed the ‘Maude Lewis Painted House Society’, hoping to preserve the house. They bought the house in 1980, but the reparation costs were too high, and so the house was acquired by the Novia Scotia province in 1984 and eventually restored. The whole house has been on display inside the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax, as part of a permanent exhibition since 1998.

Jean Cocteau was an incredibly influential French artist, playwright, poet, director and novelist. We’ve chosen to focus on his murals or ‘tattoos’ that he painted on a villa in the French Riviera. These transformed the villa into a stunning world, with Cocteau's huge, confident line drawings filling the walls of every room. While this villa wasn’t his own home, he did return to the villa every year for eleven years, decorating most surfaces of the house with his stunning artwork.

Cocteau was invited by Francine Weisweiller, who owned the villa, to stay with her after they met in 1949. Cocteau asked if he could paint something above the fireplace, and the result was a loose line picture of Apollo.

This initial mural soon lead to many more, until Cocteau had painted the whole interior of the house. He viewed these as ‘tattoos’ rather than paintings, making the deliberate choice to keep the ‘tattoos’ linear, rather than filled with much colour. He used charcoal for the black lines, then mixed pigment with milk for the colour sections. It wasn’t just walls that Cocteau painted - he also painted some of the furniture, created mosaics, and even designed a tapestry for the villa.

The villa and frescoes have been meticulously restored, and will be open to the public from Autumn 2025.

David Parr was born in 1854 in Cambridge to a working-class family, and aged 17, began working as an apprentice for a decorating firm painting houses and churches. Parr worked with the firm for his whole career, completing work for houses belonging to influential designers and architects such as William Morris and George Frederick Bodley.

In 1886, David purchased a terraced house in Cambridge and over the next forty years would use his decorating skills to meticulously hand-paint stunning patterns across the walls, transforming the interior of his family home.

After David’s passing in 1927, the house was lived in by his wife and then his granddaughter, Elsie Palmer, who lived there for over 85 years. The house was opened to the public in 2019. It’s now possible to buy tickets to visit the house to see David Parr’s stunning decorations in person.

This stunning house, in Chartres, France, built and decorated entirely by Raymond Isidore, is the result of 33 years of work.

A road-mender and later a cemetery sweeper, Raymond began collecting pieces of broken crockery and glass that he found while working - drawn to their sparkle and colour. These pieces accumulated in his garden, with no specific purpose. Then, one day he had the idea of making a mosaic with the pieces he’d been collecting, and from that day in 1938, he never stopped.

He began decorating the interior of the house with mosaics and decorative painting, covering practically every surface in the house, before starting on the exterior. The mosaics were made from pieces he collected from public dumps and the roadside, as well as broken crockery his neighbours began bringing to him. Isidore's years of meticulous work dedicated to decorating his home have resulted in one of the most astonishingly beautiful houses we've come across.

The house is now open to the public.

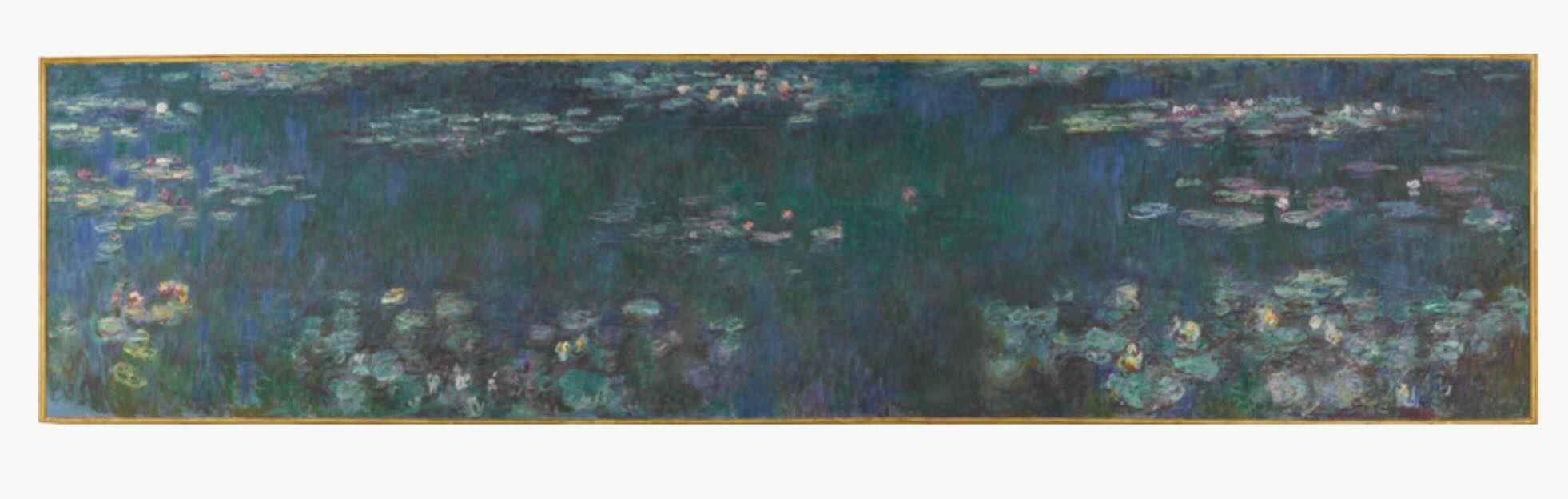

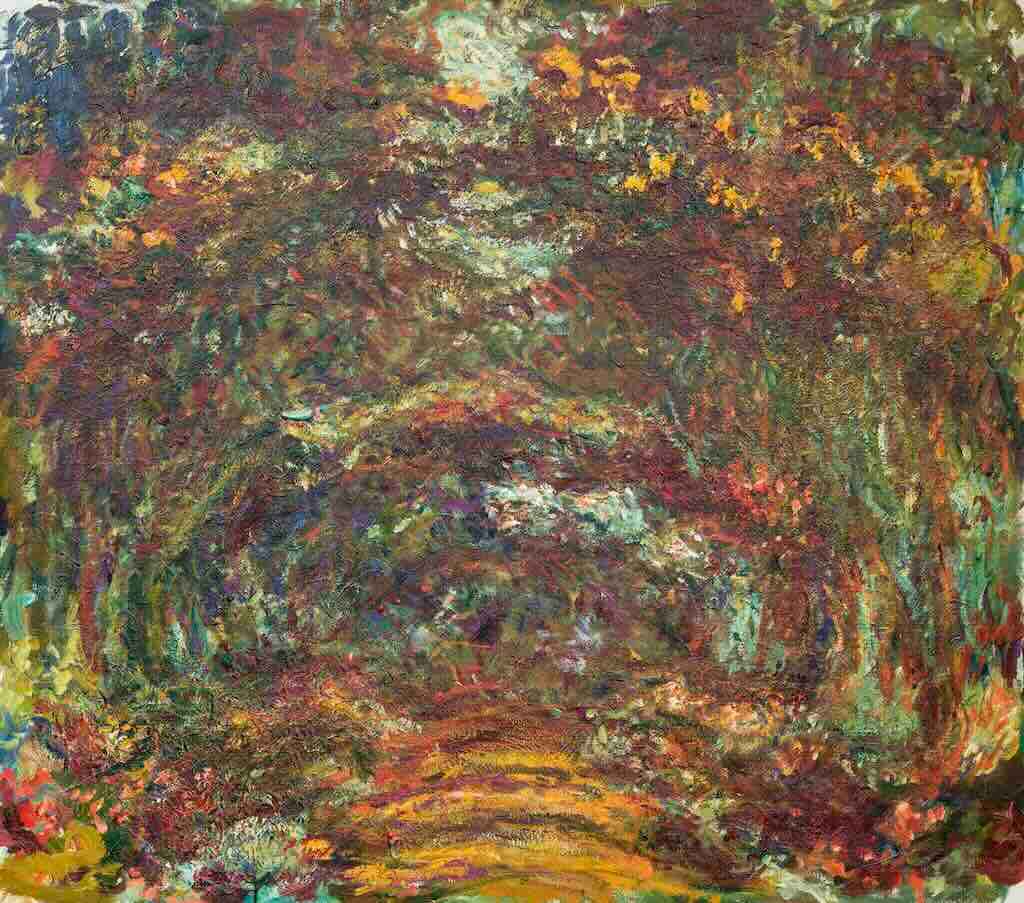

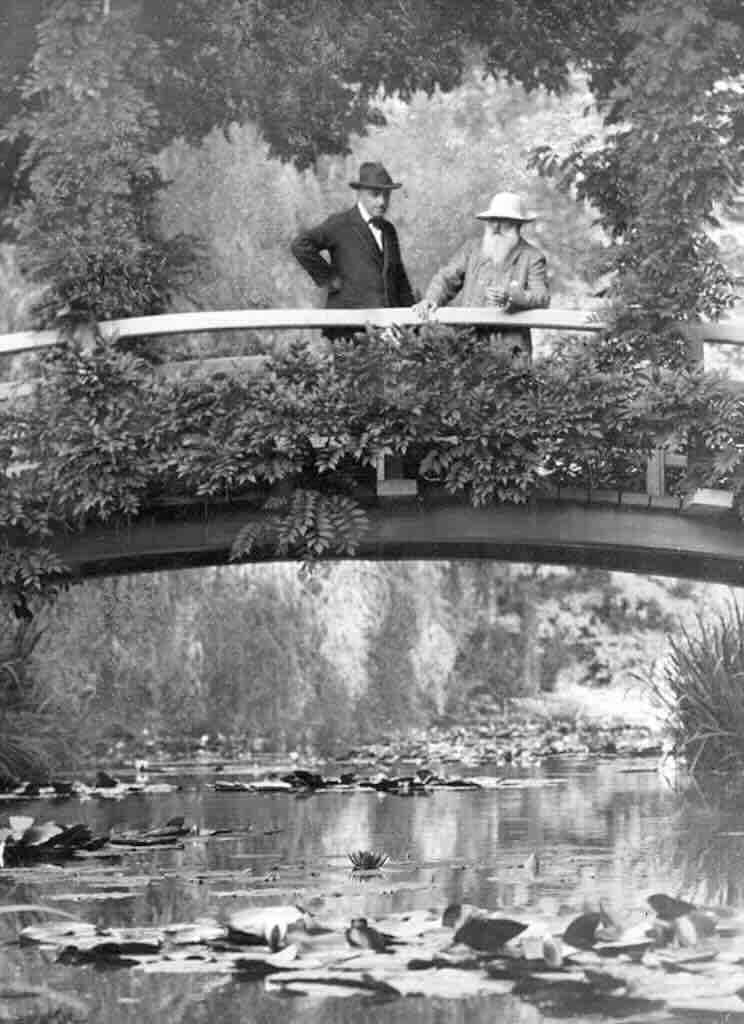

Artist Claude Monet’s house and gardens in Giverny, France, are widely known as the source of inspiration for many of his paintings, particularly his famous waterlily series.

The garden didn’t just inspire his work – he specifically created the world that he wanted to paint. In this way, the gardens can be viewed as a work of art in themselves. He filled the garden with flowers, walkways, and a pond coated with waterlilies, bordered by drooping willow trees, and complete with an arching Japanese-style bridge. Visiting the garden is like stepping into Monet’s paintings.

While Monet’s garden was the source of inspiration for his paintings, his house is also beautifully decorated, with a huge studio, and some of the rooms being colour-themed.

You can book a visit to Monet's house and garden here.

There are so many artists' homes to explore - if you're interested in reading about more examples then we recommend taking a look at this article by the Royal Academy.