Stories in Felt: Jessie Oonark and nivinngajuliaat

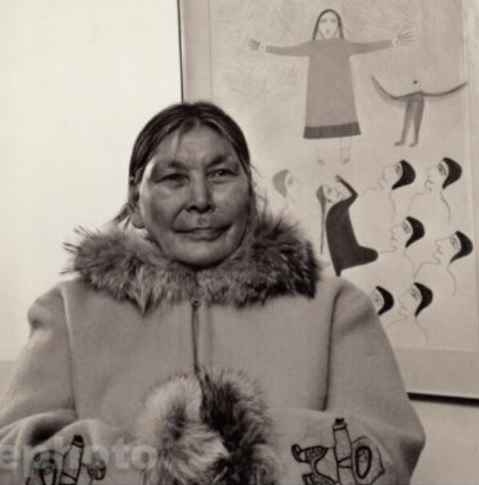

If you’d asked a young Jessie Oonark if she thought she’d become an artist someday, she’d probably have been very surprised. Growing up in Utkukhalingmiut hunting camps in Nunavut, Jessie spent her first 50 years living a traditional nomadic lifestyle in snow houses and tents. Art in pen and paper form was not something she often saw: Utkukhalingmiut culture even had a taboo against drawing images because of the belief they could come alive at night.

Textiles, however, were another matter. In fact, they were essential. Sewing was so important for survival that it was one of the first skills young children learned, but it was also a form of folk art, with skins and furs used for clothes chosen carefully for their complementing colours or arranged in contrasting bands. Inuit women shared innovative techniques among themselves, like stitches which only passed part-way through the fabric to keep clothing waterproof. This was probably one reason why, when the Canadian government started offering craft programmes in Arctic communities in the 1960s, it didn’t take long for Inuit women to create a brand-new form of textile hanging.

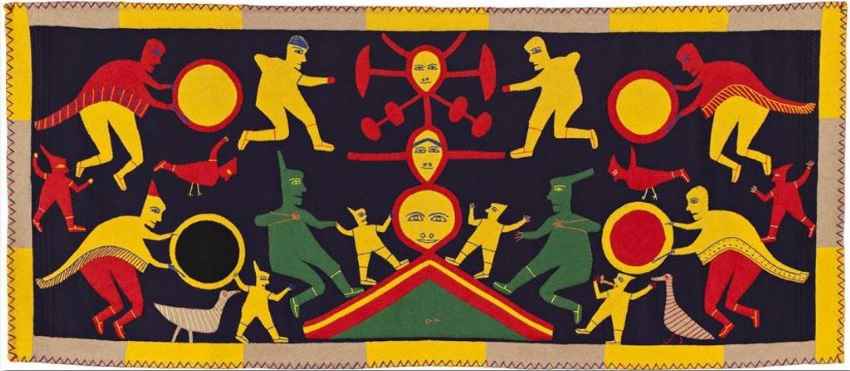

Jessie Oonark was one of these women. Relocating to the town of Baker Lake to escape a famine, she rapidly became involved in a variety of art projects. This was her first experience of formalised art, and despite being in her 50s at the time, she took to it like a duck to water. Along with her friend Marion Tuu’luq and a group of Baker Lake women, she established the new art form of nivinngajuliaat.

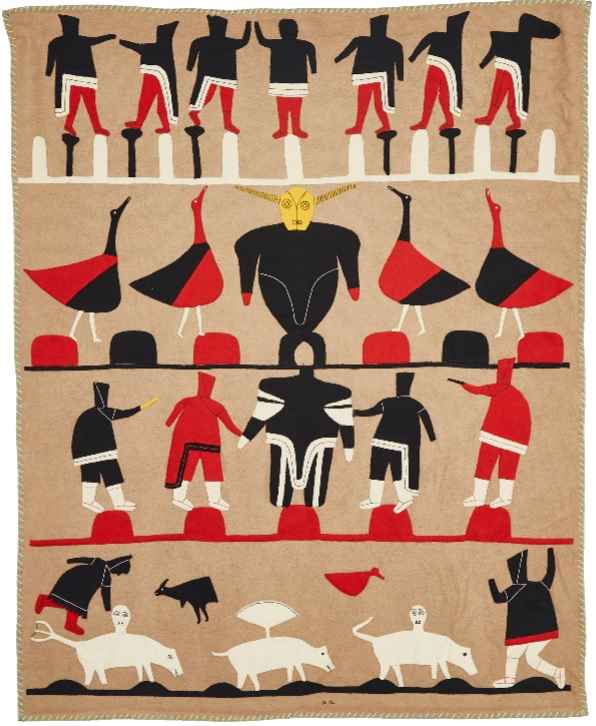

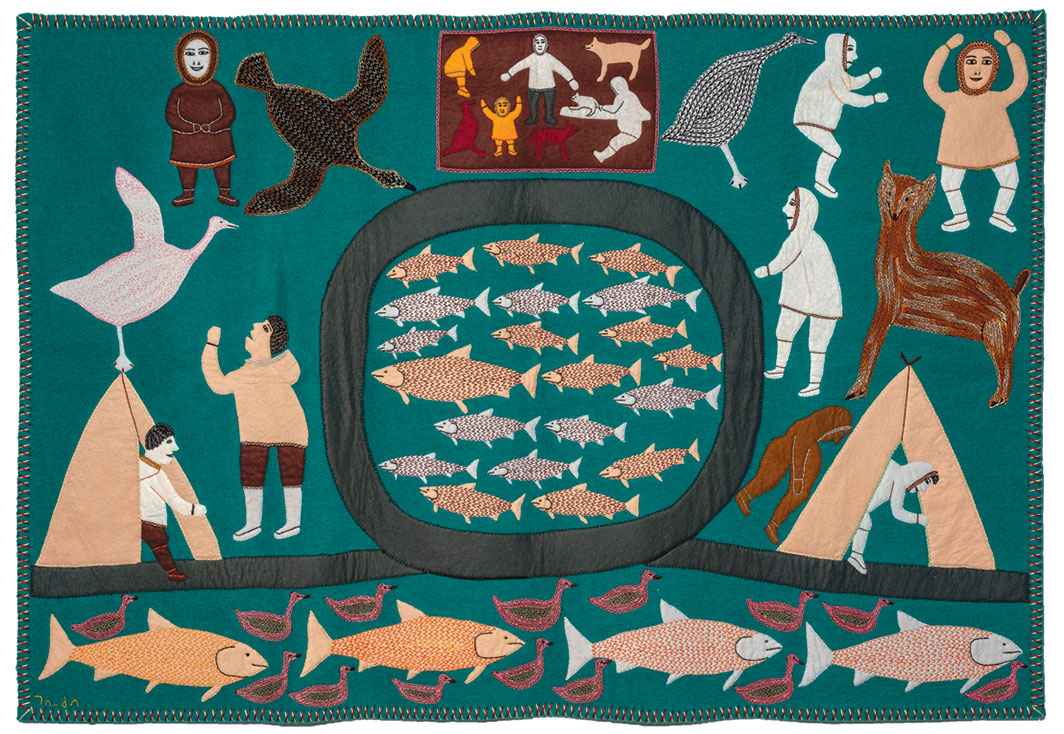

Nivinngajuliaat, or wall hangings, are brightly coloured appliqué banners featuring a distinctive embroidery style. Made using heavy woollen cloths such as duffle, stroud or felt, nivinngajuliaat depict people, animals and scenes from traditional Inuit life, capturing tales, traditions and elements of daily routines from a way of life that was rapidly disappearing.

As with many creators of naïve art, Jessie’s work is complex and open to interpretation. What the viewer sees depends on what they choose to read into it or even which way up it’s displayed. Its ambiguity of meaning lets its audience draw their own conclusions about what she wanted to portray. For example, "Two Fish Looking for Something to Eat" shows how ambiguous Jessie’s work can be. At first glance, it’s a depiction of a traditional fable about a cannibal fish – but if you turn it vertically, it looks completely different.

Like her parents and mother-in-law before her, Jessie was a storyteller. She wove elements of Inuit legends and oral tradition into her creations alongside scenes from everyday life. If you would like to find out more about inuit artists past and present, take a look at this website.

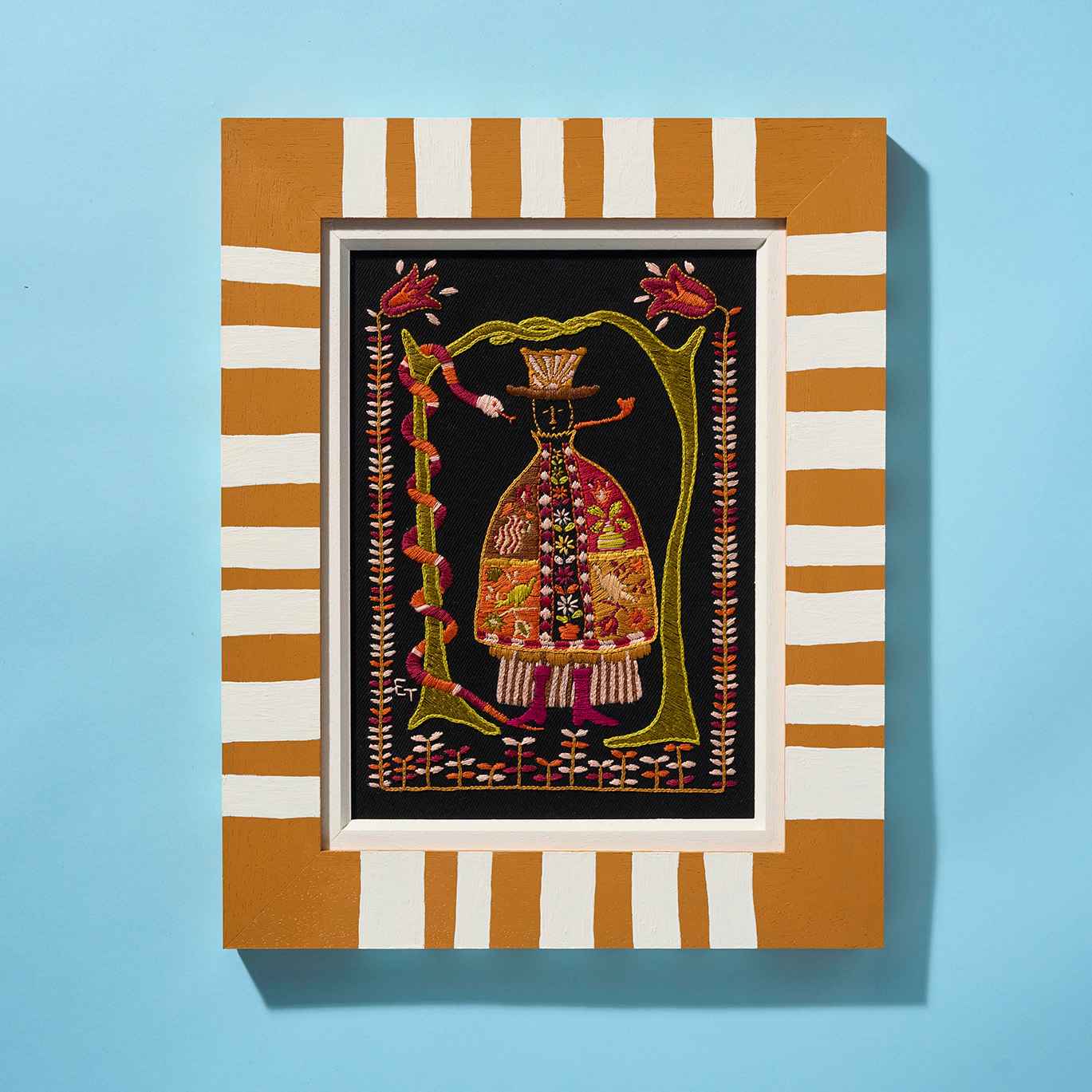

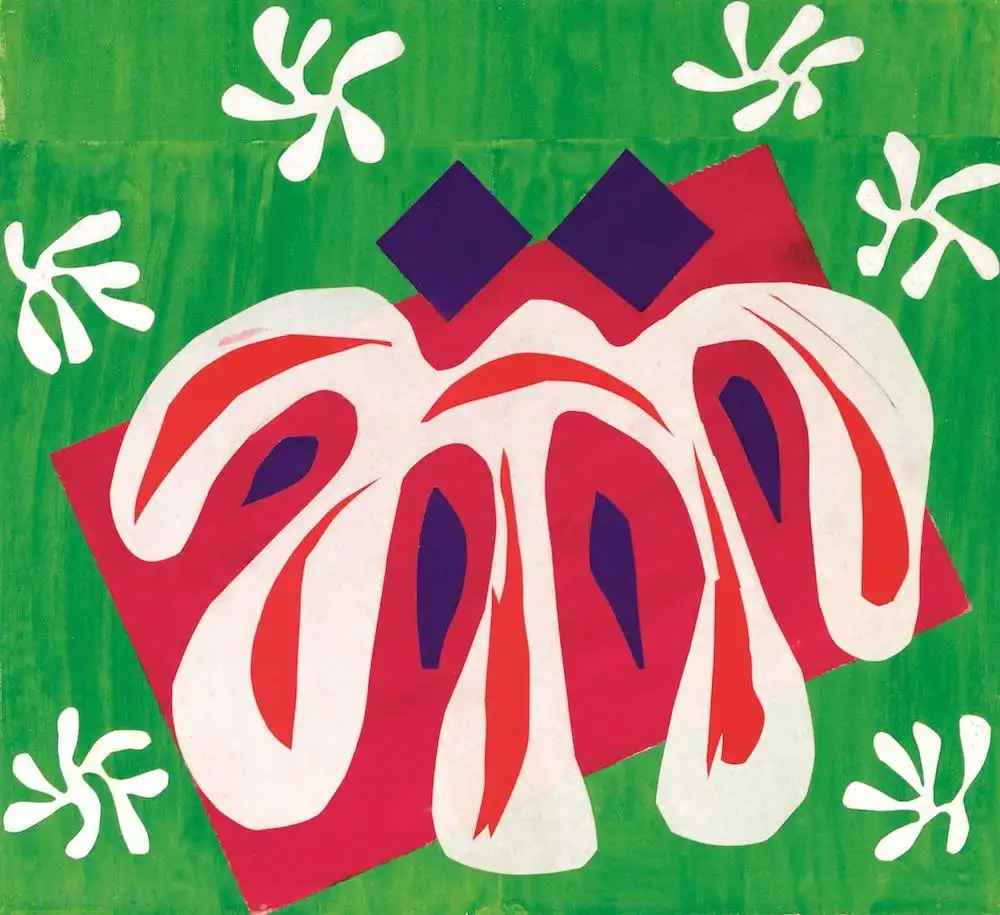

Personally, I find the narratives within Jessie Oonark and the wider nivinngajuliaat art very inspiring. Not only are the pieces beautiful, but the stories within the pieces enables a deeper connection and intrigue. This is the reason why so many of my own designs start from the stories. I love the connection that it builds between the maker and their creation. For example, this is the core basis of my signature kits, The Fables which each depict on of Aesops fables. You can see examples below along with their morals.